This is a two-part analysis:

Today, we see how electric mobility has made things equal for everyone. The technology makes things easier but also limits creativity, makes it too easy at times, and lowers the entry barriers.

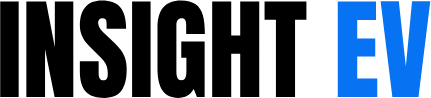

We sifted through 63 cases and tried to identify patterns. There is a huge concentration of capital deployment as the top five – two in India, one in Taiwan, and two in North America – have cornered 65% of all money deployed. What made them attractive to investors?

Electric Mobility: The Great Equalizer

Here’s an experiment: Release an RFQ for 10,000 mid-drive motors targeting 7 – 11 kW output. Depending on your geography, you would talk to 3-15 suppliers offering a spectrum of ratings, costs, and warranties. Again, depending on your state of evolution and how much of a hurry you are in, you can close the deal within 10-15 days. The motors can start arriving within a few days after that and can be deployed immediately, provided you have figured out the controller and the rest of the paraphernalia.

You can also repeat the same exercise for battery packs: say 1.5-2.0 kWh portable packs with LFP chemistry. The number of suppliers would be far smaller, but each prominent geography would have at least 2-3 suppliers willing to meet your quality and warranty demands.

Now, do the same exercise with ICE: Release an RFQ for 10,000 125cc IC Engines for motorcycles.

Good luck with that.

When your purchase team would have scouted around the globe, they would find a handful of suppliers willing to supply crate engines, most of them Chinese. The engines would be of suspect quality levels, and getting them in fully assembled form in crates would be costly. You would have no control over the refinement levels and smoothness of the engines, and defining maintenance contracts with the supplier would be a nightmare.

Nothing like that happens with electric motors or battery packs, a refreshing advantage for electric mobility.

IC engines have been through a 130-year development arc and are smoother, more powerful, and better in every way today. However, it is still nearly impossible to get one out of a crate and expect it to behave universally as any engine of that cubic capacity ought to do. A Honda engine is different from a KTM engine, and it is different from a Yamaha engine.

In contrast, motors are indistinguishable from a customer perspective. Sure, the internal workings may differ, and the efficiency may vary within a small range, but the fundamentals don’t differ much. More than the motor, the motor controller and its software have a more decisive say in fine-tuning things. And as soon as the discourse shifts to software, the fundamentals shift – everyone is an equal now.

When it comes to L-category EVs, ten guys in a garage may do better than 1,000 in an industrial estate.

That equalising nature is the central idea in electric mobility. Everyone is an equal. Stitching together a battery pack and developing a motor is far too easy. No offense to EV innovators, but when we say easy, the benchmark here is the overtly complicated, precision-engineered, high-on-metallurgy, internal combustion engine.

The other aggregates are even simpler

If the motor and battery are simple and off-the-shelf, the other components carry on with the theme.

Take frame development – an ICEngine reciprocates, sometimes at five-digit rpm crankshaft speeds. A reciprocating motion creates vibrations, which, if they remain unchecked and unaccounted for, create fatigue and failure of the frame. Thus, an ICE motorcycle frame and the engine casings must be strong enough to withstand heavy vibrations.

In comparison, electric motors are rotary, with minimal vibrations. The only source of distortion to the frame comes from the road. Those are much smaller. That means that as long as you don’t cut corners on welding, even mediocre plumbing would get you over what is needed for the frame. Hours of CAD and costs can be reduced.

This is even more profound for mopeds under 25 kph – some of the frames we see today are ridiculously simple. Yet they get the job done.

Or the transmission: Any ICE Engine has a torque modulation problem that must be compensated through a manual or variomatic transmission. The idea behind every transmission is the same – to get the proper torque and speed to the drive wheels. As a desirable extra, the transmission is expected to optimize fuel consumption and deliver on the riding experience.

For ICE engines to achieve that, the starting point is a carburetor/fuel injection system, a mechanical system controlled (in FIs) through an electronic chip. At the other end of the engine is a transmission, a complex system utilising a mix of gears/shafts/cogs/belts/shafts/pulleys. Designing one is challenging. Grinding and machining gears is costly and specialised, though suppliers are aplenty. Integrating the transmission to deliver what is needed to everyone’s satisfaction remains challenging.

All of the above, and more, is achieved in EVs through a motor controller. At the core, it is a chipboard with embedded software. Not only can it modulate the speed of the motor and help deliver effective torque, but it can also change the power output within a certain range. A controller is complex to engineer and complex to code. It is very important, especially when you want to do a motorcycle performance. How important? Let’s say one of the most impressive motorcycles we have seen in recent times is the Auper, and the CEO, Silvio Rotilli (Brazil), is a Phd in Motor controllers. The other good company we interviewed, Ryvid, offers a choice of two controllers off the shelf.

But at its heart, the MCU (no, not the Avengers) remains a tinkerable device that three guys in a garage can do. Most startups in this area have a handful of highly talented guys, not a sea of mediocrity. We have seen startups using Raspberry Pis to create their initial prototypes. When it comes to mass manufacturing, the Chinese/Taiwanese are there to support.

If the above sounds complicated, remember every motor supplier would be willing to offer you their own controller options, which would happily do 95% of what you want.

So with the frame simpler, the motor, controller, battery, and BMS, all off the shelf and easy to tinker with, electric mobility reaches DIY levels of simplicity.

EVs: The edge is Incremental at Best

For all practical purposes, E2W manufacturers can develop and industrialize faster. Unfortunately, that makes them equal, especially with core innovation moving to cell developers and motor manufacturers. In the traditional sense, the edge of one vehicle OEM over the other is never substantial. In the ICE world, Honda is known for making smooth revving engines with bulletproof reliability, and that has become the brand’s edge over others. Other brands have their own traits. As of now, the E2W world has no such distinctions. We are too early in the curve.

Any edge cannot last for long. Be it fast-spinning, lighter, more power-dense motors or high-energy-density cells, any OEM using them as an edge has a mere six months to milk the edge. The rest of the industry would get access to the technology if they didn’t, to start with.

As an illustration, maybe a startup gets first access to 15C cells with higher energy density, from Molicel, making the battery energy jump from, say, 1.5 kWh to 2.5 kWh within the same space and weight and improving the charging time to less than a minute for a full charge. Miraculously, the tech costs a dime. That is a plausible edge. Unfortunately, that edge is likely to last for six months. Cell suppliers are commodity sellers. They would offer the same tech to everyone. It’s like LED lamps in cars – Audi was the first to go full LED, but now even Suzuki scooters have them. Hella supplies many OEMs and other suppliers like Koito, Stanley, Marelli, or SL won’t be too far behind.

For anyone to stay ahead, with technology as the edge, is extremely challenging. One has to innovate every day, which is costly, and often one would find that customers are not willing to pay a significant extra for the technology edge.

Innovation in L-Category Electric Vehicles Moves Upstream

When it comes to L-category electric vehicles, innovation is pushed upstream. A stark difference exists between EVs (cars) and E2Ws/E3Ws because the latter have restricted packaging space and a constrained price spectrum. In almost all cases, there are no enclosed interior spaces, so even the UX/UI and feature set have a glass ceiling.

So what can give an electric two-wheeler an edge over the others? The fundamentals, which have dropped down from ICE machines, say:

1. More Power: People want to go quicker and faster. The common-sense way is to make the motor bigger or more power-dense. At the fundamental level, the motor is governed by relatively simple mathematical equations. Sure, all sorts of motor innovations are happening on the hardware front, but you won’t tap into any exotic stuff for a 70 kph commuter scooter. Everyone picks up similar motors, efficiencies straitjacketed within a tight band, with the price and warranty (again, price) being the key decision attributes. Also, even if you pack a higher power motor, it almost always comes at the expense of the range.

2. More Energy: People want to go further. Again, the common-sense way is to make batteries bigger, but there are two significant barriers – cost and packaging space. The latter first – If motors have a very finite practical operating space, batteries are even more constrained. A cuboid of a specific size can (say) pack X.Y kWh. You may add 5% more within the same cuboid, but not much more. Depending on the format you select, cells have a universal size. At a specific price point, they also have similar power densities. The X.Y above depends on the number of cells you can pack within the cuboid (won’t change much as everyone optimises) and the power density of each cell (can change, but you will have to shell out more). More cells also add weight and cost. Thus, within cost, packaging space, and weight constraints, it is a narrow triangle within which every battery/vehicle developer has to operate.

3. More Glitz: By glitz, we mean FFF – Feel, Finishes, and Features. The first two are highly correlated to the BoM cost. Nowadays, the third is driven by software, a great equalizer. Building an edge here without compromising on the price is highly challenging.

4. Less weight: The only thing that makes any sense. If you can’t increase power to go faster and can’t increase energy without getting heavier, then weight loss is the elixir everyone should be running after. Making everything lighter, cheaper, and stronger sounds like a good strategy. Mind you, it is not easy. At the same time, there is a lot of room for optimizing materials and geometries. The E2W industry is nowhere close to litre-class superbikes when it comes to weight optimization.

Considering the above, it is apparent that apart from frame geometries and material science, vehicle manufacturers have terrible constraints. Most innovation in the ecosystem has moved from vehicle manufacturers to suppliers and technology developers. For example, batteries can be more energy-dense and lighter, but that part of the development is dependent on new cell formats and cell chemistries, both out of the purview of vehicle manufacturers. Similarly, motors can spin faster, be lighter, employ fewer or no rare earths, deliver more torque, etc. But all of that would be done by motor manufacturers.

The innovation has moved upstream.

Electric Mobility Lowers Barriers to Entry

Electric mobility lowers the barriers for the entire industry – the next innovator would be as good as the last one.

On a macro level, (if we were to all electrify), this is a fundamental change in the character of the industry. With great equalisation and democratisation comes fragmentation. Good luck with defending that 20% marketshare if everyone moves to electric.

With equal and easy access to technology, limited vertical integration possibilities, and a finite operating envelope, it is way too easy to turn into an electric vehicle manufacturer. The only high-ticket items remain the supply chain management and manufacturing. However, the battlefield is littered with failed startups and idling plants, so even those are manageable.

Electric Mobility is Cost-Effective

Apart from being within reach for the small innovators, electric mobility is also more cost-effective on every front. Setting up a motor manufacturing line is more cost-effective than an engine and transmission shop. It’s also not too costly to make your batteries if you decide to do it in-house. Otherwise, numerous battery manufacturers have tried and tested batteries that are ready for deployment.

As long as you stay away from setting up your own cell manufacturing, developing and manufacturing any L-category electric vehicles would work out cheaper than if you were doing the same with ICE powertrains.

Where did Investors put money in the E2W Space?

We went through 63 significant investments made in L-category vehicle companies in the last 15 years. Most investments were in the electric two-wheeler space, though we keep getting three-wheeled, reverse-trike oddities like Arcimoto and Apterra from the US. Also, significant investments have been made in India’s commercial electric three-wheeler space, and they are part of this analysis.

Rules of Analysis

While selecting the investment cases for this analysis, we considered specific cases only, selecting them based on the following criteria:

1. Only equity investments have been included.

2. Grants have been considered, but the calculations do not include debt.

3. In case the companies did an IPO, the cash raised by the company has been considered.

4. Regarding SPACs, the best-case estimates of the actual investment that went to the company have been made.

5. We have tried to include only pure-play vehicle manufacturers as part of this discourse. Some companies plan to deploy fleets or battery swapping networks, but we have excluded them.

6. #5 leads to some anomalies. Gogoro is a vehicle manufacturer, but it is primarily an energy business. Yet, we have included it as, without the scooters, the swapping network would have been useless. Similarly, we have included African players like Roam and Ampersand as they developed a motorcycle and deployed a swapping network. In these cases, more of the capital would be deployed for the swapping network and very little for vehicle development. This skews the analysis somewhat.

7. However, we have excluded India-based Yulu/YUMA Energy and many more similar players as they are fleet deployers and not vehicle developers.

8. We excluded several India and ASEAN-based startups that were more Chinese white-labelers than vehicle developers. Kinetic Green has been considered, even though its initial scooters were Chinese kits imported and assembled; its present portfolio has vehicles explicitly developed for the company.

9. We had to exclude entirely held companies like Vinfast, as it is nearly impossible to ascertain how much investment their parent puts into them. This skews the analysis.

10. What also skews the analysis are players like Spiro (Africa), which have significant debt funding compared to their declared equity funding. We have only considered equity funding for our study.

Investments by Company

Analysing the 63 investment cases, we counted a cumulative investment of USD 5.87 billion from private and public money. Of this, nearly 65% was cornered by the top five (in terms of share in global funding).

None of the top five is doing well in making profits or in return on investment.

Let’s look at what made the top five attractive to investors in the first place.

Ola Electric

In our study, the biggest beneficiary has been India-based Ola Electric, which accounted for more than 25% of all investments in the sector globally. India is the largest two-wheeler market in the world, and any manufacturer with a significant plan very early in the market growth curve has the potential to attract investment. That’s what happened with Ola Electric.

What also worked for Ola was the early involvement of large investors like Softbank, which was already a major investor in the group’s ride-hailing business. Over multiple rounds, the company also saw participation from Tiger Global, Temasek, Hyundai-Kia, and Alpha Wave.

We estimate that Ola raised USD 899m in private funding and another USD 571m in the IPO.

In attracting the quantum of investment that Ola Electric did, the company weaved together a story that was received positively by private money. The company announced plans for the world’s largest two-wheeler plant with a 10m capacity, even though the installed capacity has been less than 1m units. It seemed illogical considering most OEMs try to spread manufacturing geographically to optimise logistics costs, and plants beyond 1-2m capacity have limited volume benefits. The investors did not notice.

Further, Ola focuses on vertical integration and is setting up its own cell gigafactory. This is a capital-intensive approach and works well if you have very dominant market leadership. As we mentioned earlier in this analysis, due to the great equalising nature of the industry, a dominant market leadership is not achievable in today’s world, especially for a startup. Capital-intensive back-end integration has little value without a dominant leadership or very large production volumes.

What made Ola attractive?

1. The perceived fast execution promised by the founder.

2. An acquired, fully developed scooter platform.

3. The fact that the ICE incumbents in the industry were still not aggressive when it came to electric scooters.

4. That the Indian market was flooded with cheap Chinese scooters, and there was space for better products.

5. The gig economy and ride-sharing were just taking off.

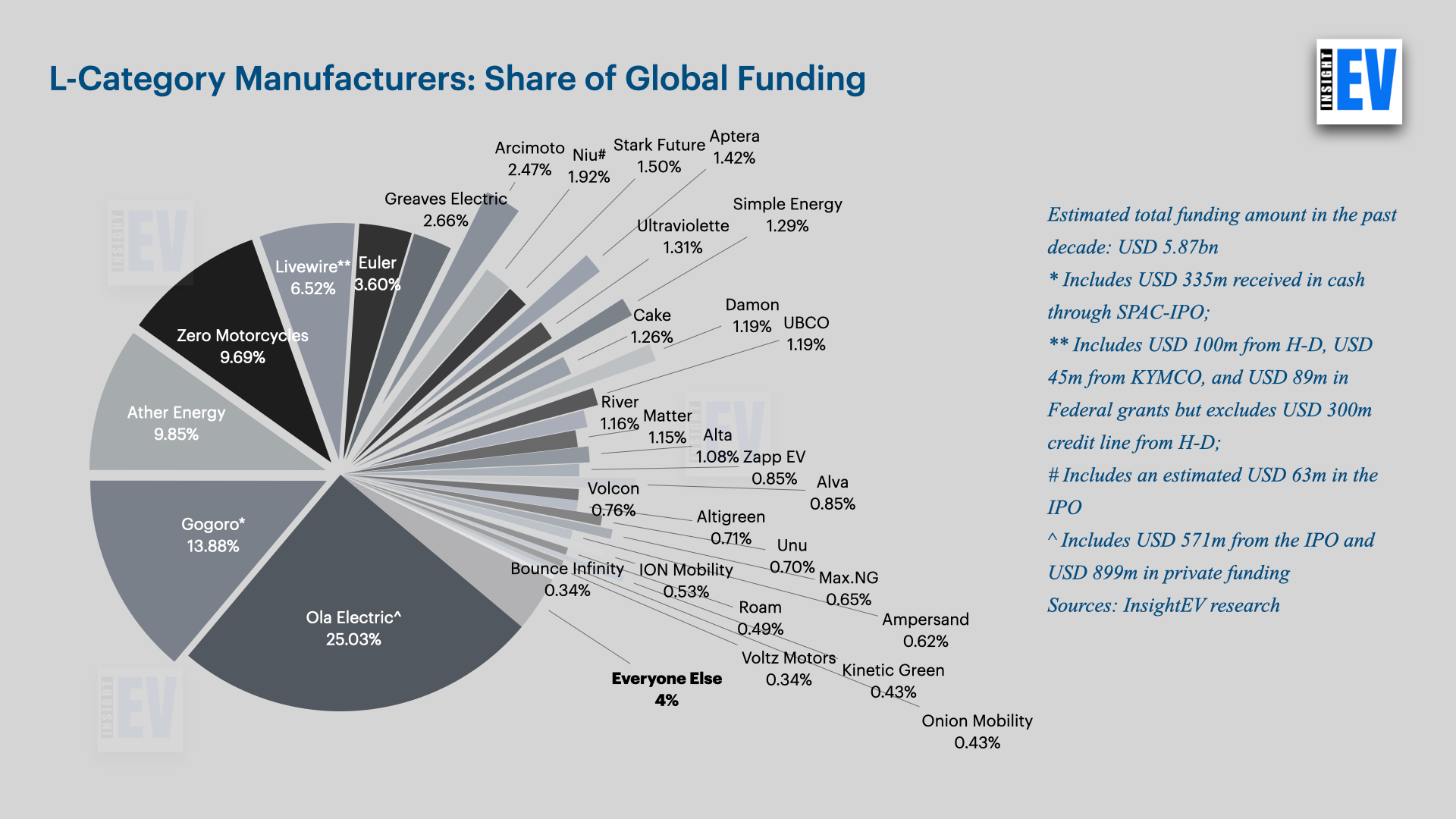

The back-end integration becomes even more questionable when the global prices of the backend (batteries) crash. With China flooding the battery market with its over-capacity, battery prices continue to crash: Bloomberg NEF estimated cell prices at USD 78/kWh at the end of December 2024.

In such a scenario, matching FOB battery prices from China with locally made cells from a factory that would take a few years to reach maturity would be highly challenging. Either way, the drop in battery prices works to everyone’s advantage, but it works against Ola.

Ola’s cell gigafactory is still under construction and is expected to commence production in the coming months. The company would be making 4680 format NMC cells to start with.

In planning a large two-wheeler factory and a cell gigafactory, Ola was piggybacking on the Indian government’s Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes. Ola received PLI for its two-wheeler production, which has been going according to plan. The company is also a participant in the Indian-government’s PLI-ACC (Advanced Cell Chemistry) scheme. However, with delays in getting the cell gigafactory to start production, Ola has missed milestones and may face challenges in claiming PLI.

Ola Electric did an IPO in 2024, considering that private money had dried up. While the company is yet to make any profits and would unlikely make any for the next few years, the early investors up to Series C have made returns through the IPO.

Gogoro

For a long time, electric two-wheeler mobility was defined by Gogoro. The Taiwan-based company was one of the earliest technology and business model innovators in the segment. When the world was dominated by cheap Chinese-made scooters, most still energized with lead-acid batteries, Gogoro exploded on the scene with a good-looking scooter, high-class engineering, Li-ion swappable batteries, and a swapping network that would comprehensively cover Taipei City. With its candy-like batteries, Gogoro exuded an almost Apple-like coolness.

Investors loved it. They still do. Over the years, Gogoro has raised USD 815m in funding, including USD 335m in cash raised in the IPO. Even post IPO, Gogoro has raised equity funding from Castrol and more money from its promoter, Ruentex Group.

What made Gogoro attractive?

1. A well-designed product and quality of management.

2. A battery swap model that was innovative when it came out. It offered users the freedom to use the scooters indefinitely without range anxiety.

Apart from the Ruentex Group, Castrol, Temasek, Sumitomo, Foxconn, and many more prominent investors are on Gogoro’s captable.

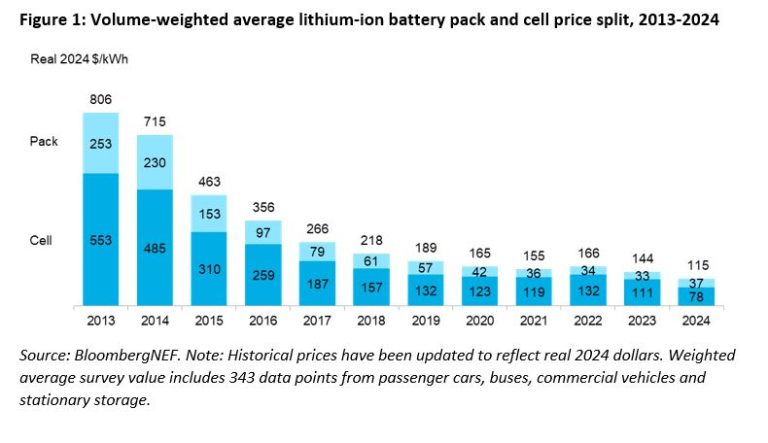

However, Gogoro is still a loss-making company. Its international expansion has been slow at best, and any expansion is cash-intensive. We have questioned the business plan previously.

From what could have been a class-leading premium scooter manufacturer, Gogoro has instead positioned itself as an energy company. That sounds great – we estimate that it has the biggest battery swapping network in the world, though 95% of that network resides in Taiwan. However, being an energy company comes with its challenges. Gogoro offers its swapping networks to other brands (competitors) to bring more customers. Not only that, Gogoro has also shared its hardware (motor and electronics) for others to develop their scooters.

As a result, there are seven more brands in Taiwan that use the Gogoro battery swapping network. The market they have captured would have been Gogoro’s. Battery swapping revenues have increased while hardware (scooter) sales have declined. The increase has not compensated for the decline, and overall revenues have been dipping.

Carmakers and two-wheeler manufacturers would want a chunk of their revenues to come from subscription products. That’s what Gogoro’s battery swapping business is. However, that comes at the expense of scooter sales, which is mind-bending.

Swapping Networks appears to be an elegant solution—for the user, it frees them from range anxiety. For the deployer, it guarantees long-lasting revenues. However, they are capital-intensive and put depreciating assets on your books.

Gogoro says that as of December 2023, they had deployed 12,000 battery racks at 2,540 locations in Taiwan—the user is never more than a kilometer away from a swapping point.

In doing so, the company has raised USD 1.1bn in funds. With an estimated USD 120m cash left on its books, it seems Gogoro has run through USD 980m of money in making the scooters and setting up the swapping network. The company’s 2023 annual report puts the value of its deployed battery packs at USD 380.3m. Between the racks and the batteries, not counting the charging station infrastructure, the batteries in transit, the batteries written off, and the associated manufacturing equipment, there is a capital deployment of USD 500m in Taiwan alone.

The capital-intensive nature of battery swapping also hinders expansion. Gogoro has been trying to expand in India, Indonesia, and Mainland China. However, all such efforts have been slow-moving and, in some cases, aborted.

Ather Energy

India’s oldest E2W startup, Ather Energy, is ranked third in the study. It has managed to raise USD 578.4m, 9.85% of all capital raised. While the gap between Ola and Ather appears very large, it is not. Ather is planning an IPO in the near future, and we estimate the company to raise USD 350m, taking the total capital raised to USD 928m.

Unlike Ola, which has raised money from private investors, Ather Energy has raised significant capital from Hero MotoCorp. Till now, Hero MotoCorp has invested more than USD 100m in Ather Energy, participating in various rounds, and now holds 34.3% of the company. For the purpose of the IPO, HMC is listed as a promoter and is not selling any shares in the OFS component.

Apart from HMC, Ather counts GIC, Tiger Global, and India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund (NIIF) on its captable.

What made Ather attractive?

1. Quality of engineering development and management.

2. Entering the market very early in the curve.

3. The promise to bring ‘Apple cool’ into commuter scooters.

Like Ola, Ather makes losses. However, there are stark differences. Ola targets the bottom of the market, and Ather targets the premium segment. As the market goes through a transformation and greater fractionization, we find Ather better placed to defend its market niche. It may sound ironic here, but Ather faces almost no competition in its small niche – high quality, high tech, reliable – that it has created. The future won’t see much change, as the barriers to entry are high in that micro-niche.

Ather’s losses are more profound than the revenues. For FY 2024, the company reported revenues of INR 17.54 bn (USD 206m). Against that, it made losses of INR 10.6bn (USD 124.6m), a negative margin of 60%. Arguably, these financials are old as FY 25 has just ended, and Ather’s sales volumes have steadily improved in the last year. However, this does indicate that Ather has a BoM cost problem. We are not saying they have a pricing problem – they are already the most expensive in the market and cannot go any higher.

Zero Motorcycles

Before we talk about Zero, we want to remind you about Energica. It has not received any offers yet again. This is the condition of Energica. Scratch that! This is the condition of the entire electric sportsbike industry. Here is an Italian electric superbike brand, which had been around for many years, ran the Moto-E for some time, was supported by an American PE firm (Ideanomics), and has now gone bankrupt. They cannot find buyers for their assets at even EUR 4.275m.

Now, with that context, let’s talk about Zero.

In the early days, Zero Motorcycles ticked all the right boxes: A founder with NASA on his CV, a base in California, developing electric motorcycles that were fast and looked good, a high margin, a six-to-seven-digit global TAM volume, etc.

To its credit, while prospective rivals like Brammo, Damon, Alta, and Lightning kept on coming up with promises, or were stillborn, Zero has been the only stable manufacturer of large electric motorcycles, stable enough to last more than 15 years, even with a sales volume that remains small and highly North America-centric. They also remain highly dependent on fleet sales.

What made Zero Motorcycles attractive?

1. Product and engineering development capabilities.

2. This was back in the day, and there seemed to be a promise that Americans would take to high-priced electric motorcycles.

3. These were the good days, and private funding was relatively easy.

We do not have Zero’s financials, but we estimate them to be under USD 100m in revenue. We estimate retail sales to be around 5,000 units, though this may improve as Zero has launched Zongshen-manufactured, smaller products at a lower price point.

For a California-based company with very limited sales volumes, profitability is questionable.

What has worked for Zero as a company has been finding strong financial backing from large investors. The Invus Group, which controls Zero Motorcycles, has been an investor since 2008 and has participated in every round. Along the way, Zero has also picked up smaller investments from Exor, India-based Hero MotoCorp, and Polaris.

The Polaris and Hero relationships are important: Zero supplies powertrains for Polaris’ electric side-by-sides & UTVs. It fills a void in Polaris’ portfolio, considering that the UTV manufacturer has had little success with its own electric trysts.

The Hero-Zero partnership should be very complementary. The Indian manufacturer is known for making small-capacity IC Engine motorcycles. Zero is at the other end of the spectrum, making large-sized electric motorcycles. There is a huge market in the middle that both can exploit together.

But support from Invus is the most important. Not only has the venture capital firm invested in Zero since Day 1, but they have also come up with capital when it seemed the most explicable ask amidst an industry downturn. For Invus, at times, it seems like throwing good money after bad because if Zero faces liquidity issues, Invus would also lose the earlier investments.

Zero’s biggest weakness has been clinging to an aging range that does not set the sales chart on fire. They have been targeting eco-friendly Ducati buyers. Energica looked for the same guys, but there weren’t many.

The brand has steadfastly remained North America-centric, and the recent shift to smaller products has come with the company’s back against the wall (arm-twisted by Invus?). Most Zero products do not exceed the competition in performance, whatever little there is. There are no Zero products, except the Zongshen-sourced XB and XE, that target daily users or entry-level users.

With newcomers like Ryvid now offering good America-made motorcycles, Zero’s only strength remains attracting ample capital.

Livewire

If Zero has a solid financial backing, Livewire is on even firmer footing. It is owned by H-D. We wrote a full analysis on it some time back.

Livewire started with a bang with its operations out of Silicon Valley. It was born when Harley decided not to invest in Alta and instead set up its own electric motorcycle unit. The result was Livewire. Over the years, the company has been listed on Nasdaq and raised an estimated USD 383m from investors, the leading investors being Harley-Davidson and KYMCO. Apart from the equity investment, Livewire enjoys a USD 200m credit line from H-D.

In short, it won’t run out of cash in a hurry.

What made Livewire attractive?

1. Livewire never followed the traditional startup route, born as it was as a division of Harley-Davidson.

2. With climate and environment being popular buzzwords in those days, America was supposed to grow an immense fondness for large electric motorcycles.

The first motorcycle, Livewire One, was a slow seller, but the company believed that the S2 platform would create more affordable and mass-market motorcycles. The S2 was innovative, and even though Damon had been talking about a battery monocoque for a long time, Livewire took the setup to production with the S2.

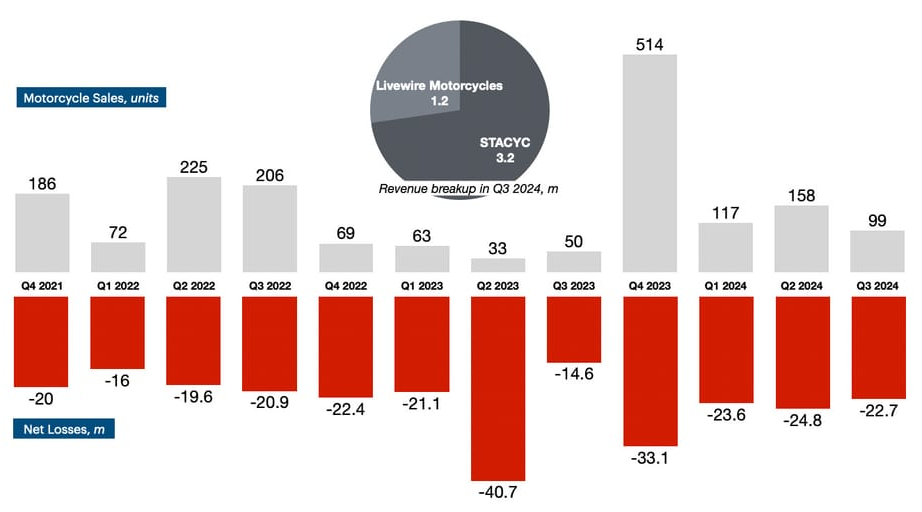

However, sales have not taken off despite the S2 now being the base for three production models – Del Mar, Alpinsta, and Mulholland. Cumulative sales over the last four quarters have been 888 units.

Meanwhile, Livewire has been bleeding heavily every quarter – cumulative losses over the last four quarters have been USD 104.2m. They may not face a cash flow problem, but the cost-cutting mode has been triggered. The Livewire team has already been moved from Silicon Valley to the H-D offices in Milwaukee.

In the second and concluding part of the study, we look at:

Which geographies have received the most investments? Why? What makes them attractive is the size of investments they attract. Also, what are the patterns when looking at investments within the same geography?

The wins & losses, and scores as they stand today. With the equalization in tech, the industry’s and investors’ focus is changing from technology and product development to deployment, asset management, and asset financing.

Do large investments in a few companies hurt the overall ecosystem?